Digging Deep: A Shared Community as Tough as Lead

"You can do more than you think you can"

Two years ago, I stood at the start of a 3.1-mile race with nothing but a water bottle and a pair of Walmart running shoes to indicate I belonged in this undulating mass of athletes and far thinner running enthusiasts. The only thing I could hear was the sound of a heavy guitar riff blaring through my Skullcandy headphones as I had chosen just minutes before to completely drown out the sound of the crowd and announcers (due most likely to a deep-seated fear I wouldn’t be up to snuff by the end of it all).

"Ask nothing from your running, and you'll get more than you ever imagined." —Christopher McDougall, Born to Run

"Ask nothing from your running, and you'll get more than you ever imagined." —Christopher McDougall, Born to Run

The truth was, standing there at 370 pounds, afraid I wouldn’t cross that finish line, I had no idea just how important this sport I had begrudgingly clung to only months before would eventually become to me—let alone the vast connections it would ultimately have to my future role as Editor in Chief of a drilling magazine. But to break it all down, we need to go back to the very beginning—and I’m not talking about my beginning either.

A ‘Long Shot’ Legacy

It’s August 3, 1974, and a man's heavy breathing can be heard faintly along the Sierra Nevada Mountains’ rocky trails. A horse lays defeated in the river not far behind, and the man knows it’s not long now before that horse—and perhaps himself, too—falls victim to the unforgiving nature of one of the most rigorous races in California, the Western States 100. However, this man, 27-year-old Gordy Ainsleigh, isn’t meant to be in this race at all. In fact, Ainsleigh is not one of the few but rather the only human being to have ever entered the 100-mile race on foot, and confidently (and perhaps in a bout of cockiness), he now pushes on up Devil’s Thumb, a 1,800-foot ascent over 1.8 miles.

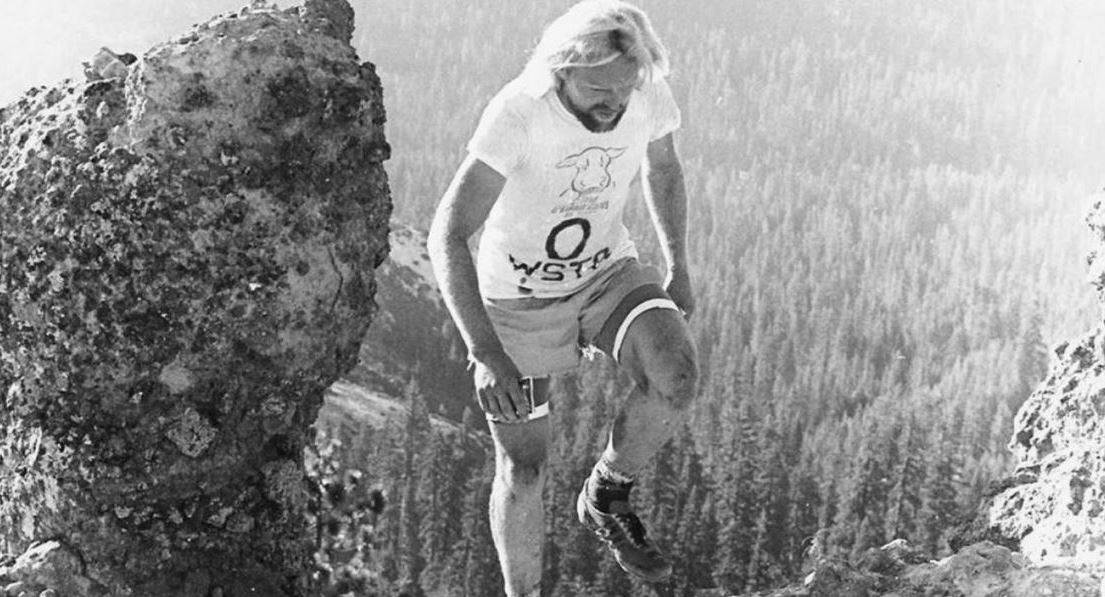

Gordy Ainsleigh climbs onward at his first 100-mile race on foot.

Gordy Ainsleigh climbs onward at his first 100-mile race on foot.

The Western States 100 was created in 1955 by Wendell T. Robie, who wanted to prove that horses could still cover 100 miles in a day—but a young and relentless Gordy Ainsleigh chose to take it one step further by proving that humans could do it too. Not only did the young ‘buck’ finish within the 24-hour timeline, but he also unwittingly began a tradition that is now worldwide and boasts a community of well over 600,000 people—which I would have once told you were complete and total lunatics.

The Leadville Legacy: ‘Lead’ing the Way

But this is just the start of our story. To ‘strike gold,’ we must now run 950 miles east to the highest incorporated city in the United States—Leadville, Colorado. When looking at the town’s rich history on History Colorado, you will find that Leadville sits at an impressive elevation of 10,152 feet in the central Rocky Mountains and was first established in the 1870s after a substantial silver boom brought prospectors from all across the country to the humble town.

During this period, mining and mineral exploration were the leading sources of wealth in the small Colorado town, and just about every family made due by working within the mines and seeking out gold and silver. After World War I, the wealth in Leadville declined, but the rise of the Climax Molybdenum Mine nearby helped to ensure that the town remained tied to mining. However, it wasn’t until the 1980s that this town’s most exciting and unique story of change and perseverance would begin.

To paint the picture, the 1980s in Leadville is just about as heavy as a brick of lead. Why, you might ask? Well, sadly, the town was in rapid decline. This decline was in part due to “The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) declaring the area a Superfund site in 1983.” This declaration was particularly damning to the people of the town as it was an unjust opinion that was held by EPA officials and not the townsfolk let alone the scientific professionals that surveyed the town. The people of the town now found themselves without jobs and struggling to make do as a town genuinely built on the principles of hard, honest work in the mining field.

Even after a decade of restoration from the townsfolk, the town struggled in ways anyone could see from a mile away—including Ken Chlouber, a man just about as tough as a brick of lead.

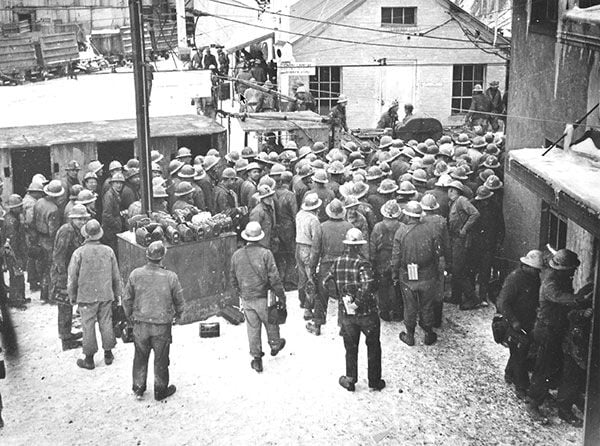

Miners in Leadville; Source: Leadville Herald

Miners in Leadville; Source: Leadville Herald

The year is 1982, and Chlouber, just like most of his Leadville counterparts, works for the Climax Molybdenum Mine. His job as an underground shift boss is one he takes very seriously, arriving roughly a half hour before his shift begins each and every day just to prepare for the night ahead and listen to the updates from the other shifts before him. However, despite his tenacity and the tenacity of his fellow mining professionals, the mine was shut down on a whim, and in the blink of an eye on a cold Leadville night, over 3,200 mining jobs were lost, and the unemployment rate in the humble Colorado town skyrocketed to 90%. Reminiscing on this dark day in Leadville’s past, Chlouber shares, “After all those years, the mining was done…We had meetings in town. What are we gonna do? Everybody had an idea but none were very good because everybody was leaving town as fast as they could." This kind of loss is exactly what turns mining towns into ghost towns overnight, and Chlouber as well as the rest of the determined Leadville residents aiming to stay in their humble town knew this all too well.

As Chlouber stated in an interview with Trailrunner, “The hurt didn’t stop there, either. Production tax from the mine paid 86 percent of the town’s property tax. Next came the huge tax shift from the mine to Leadville residents, who had lost all ability to pay it.”

Being a Leadville County Commissioner, Chlouber knew that the town had to find a means to survive, and, in their search for an answer, the town council hired an economic developer. This is when the facts were laid out for Chlouber and the rest of Leadville to see. As Chlouber puts it, “We had our mining heritage, and we had our mountains. We needed something that would hit both of those.” In their search for a solution, Governor Dick Lamm stated to Chlouber, “You need to get people here, and they need to spend the night.”

Making Friends With Pain

With this salient advice ringing in his ears, Chlouber began to think about how his rough and ready town of humble homes and hardworking miners could be transformed into the hottest travel destination of the 1980s. With picturesque resort towns like Durango, Ouray, and even Boulder just hours away, how could they possibly make a name for themselves and save their town infrastructure and community before it was too late? That’s when the ingenuity and wit only a true miner could possess took hold of Chlouber and gave him an idea that would put Leadville on the map for decades to come.

A participant and his donkey compadre at Leadville Boom Days

A participant and his donkey compadre at Leadville Boom Days

You see, Chlouber wasn’t just a miner. Unsurprisingly, Chlouber’s life outside of Climax was far more climactic. In the 1970s, Leadville was a town that celebrated its mining history with an annual event called “Boom Days,” in which Chlouber, along with several other men in the city, would participate in a burro race. The goal of the race? To prod a donkey up and down the steep and unforgiving peaks of Leadville in altitudes that quite literally were made to crush runners under their boot. And this was just the tip of the iceberg for the mountain bike racing and trail running endurance nut Ken Chlouber.

So, naturally, when faced with the unbelievable feat that was Gordy Ainsleigh running the Western States 100 and beginning a yearly tradition for trail running junkies looking to test themselves on unforgiving terrain designed to crush you, only one place and one idea came to Chlouber’s mind.

How could Chlouber effectively save his town and give back to a community of runners he proudly called himself a part of to some small degree even back then? Easy. Start his own 100-mile race on the toughest terrain in America with the highest altitudes and, given the extremity, welcome these weary travelers with open arms to rest for a night (or week) as tourism boomed in its wake.

Merilee Maupin, 'First Lady of Leadville'

Merilee Maupin, 'First Lady of Leadville'

To help with this lofty goal, Chlouber joined forces with a truly formidable team of visionaries, including Merilee Maupin, the local travel agent with a true heart of gold. Together, the unlikely bunch devised the Leadville Trail 100, a 100-mile foot race at altitudes above 10,000 feet. And, despite varying degrees of skepticism and criticism along the way, the first year began with 45 runners, none of whom died, and many of whom would return to run it again year after year.

Over 40 years later, the race continues to be a success, with around 800 athletes typically running the race and helping bring in approximately $15 million in revenue for Lake County annually. And, while mining in the town seemed to be replaced by tourism and trail running, the same energy of determination, persistence, and effort remains. Merilee Maupin claims this success is built on the energy of the town itself, "The magic of the Leadville Trail 100 is not just about the race, it's Leadville, it's the history of Leadville. Leadville is the highest town in the nation. It's a town that just reeks of strength of determination, of people that came here, seeking their fortunes."

Highlights from the Leadville Trail 100 throughout the years

Highlights from the Leadville Trail 100 throughout the years

As Chlouber continues to chant with the crowd before every year’s race begins, “I will commit! I will not quit!” This is the mantra that defines this persevering town of survivors and thrivers.

This is where it all comes together. The lives of runners and mining professionals may differ in many ways. Still, one thing that remains the same is their ability to withstand all conditions, push past all obstacles, and find the right path forward in any situation. As Maupin explains, “All the same ‘dig deep, grit, guts, and determination’ that it took those early miners in Leadville to strike it rich is the same thing for our Leadville family striking it rich with a belt buckle."

When addressing the undulating mass at the start line of his own 100-mile creation, Chlouber once stated, “Dig deep into that inexhaustible well of grit, guts, and determination.” This is what it takes to toe the line of any race and believe with all of your might that you will cross that finish line victoriously.

And, of course, if you’re one of the lucky runners that get to cross the finish line in Leadville, you can expect a big warm hug from Maupin as well, as she says, "Every year we think it's kind of like one of the world's biggest family reunions and all our runners and riders come back to town and it's just such a special occasion."

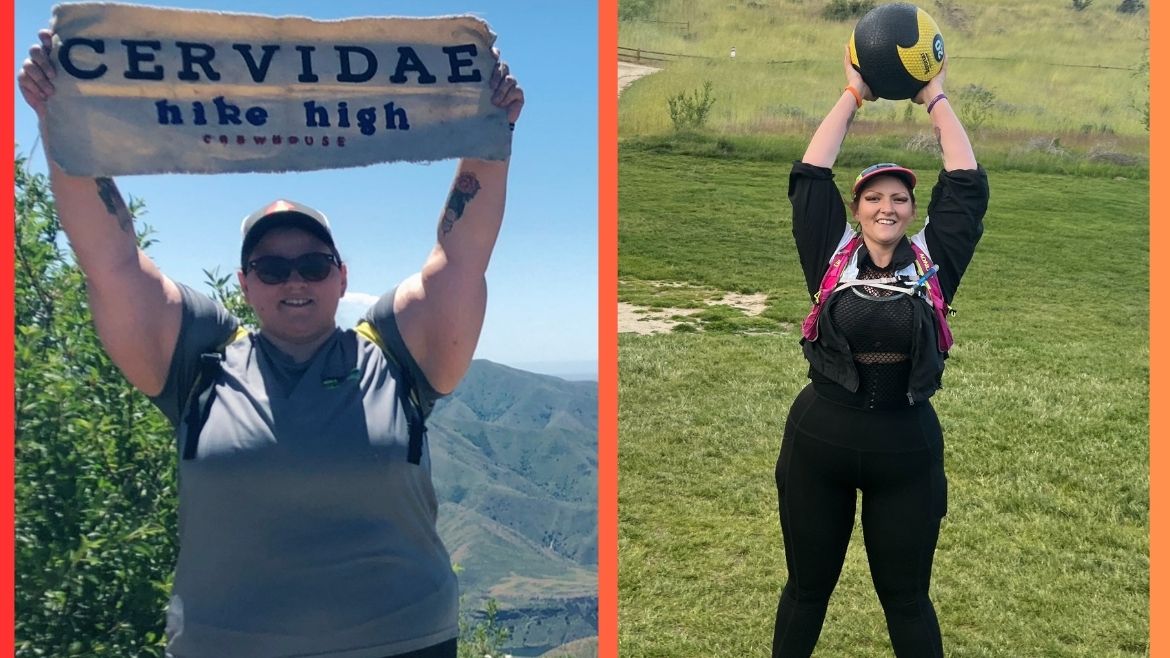

Before finding a sense of purpose versus after

Before finding a sense of purpose versus after

‘Striking Gold’ in Leadville

Now, let’s return to 370-pound me at the start of a 3.1-mile race, sweating bullets. That was the first race of many to come. I began signing up for one 5K race every month which then led to one 5K a week and then one 10K a month. Pretty soon, I was participating in half marathons every month and training for a marathon. Now, I have a medal wall about as heavy as a brick of lead on my wall, I’ve lost over 180 pounds, and I am not just preparing for an upcoming marathon but also actively training for an ultrarunning future. I’d like to say it was a magic pill or a special diet that transformed me but truly, it’s all thanks to that ‘inexhaustible well of grit, guts, and determination’ which Ken and Merilee have always known defines both the ultrarunner and the miner alike.

At the end of my interview with Ken and Merilee, I not only found myself laughing heartily with them as if they were old friends but also dreaming of a future with Leadville in sight. That’s when these two amazing people showed me once again just what makes this sport and this industry so synonymous with my own passion and determination.

As our interview concluded and I shared my story with these ultramarathon icons, Merilee began to talk with me about the Leadville lottery. In that moment, Ken asked if I had signed up for the lottery that year to which Merilee explained I had not. Ken laughed, “Oh, you wussy! You need to do it!” I chuckled, thinking about how long I had sat on my couch watching video after video of ultrarunners taking on this prolific race from start to finish.

Then, Merilee did the unthinkable and offered me a secured Leadville Trail 100 Legacy charity slot in the race for 2025 and, before I could even think of a lousy excuse, I said it was a done deal and I’d even opt to be a scholarship runner and try to raise the $2000 for their Legacy scholarship program.

Leadville-bound in August 2025!

Leadville-bound in August 2025!

Now, you might be thinking to yourself, “Well, you can always make a promise and just break it.” But, if you think I’d break my word like that to two people I admire this much, you clearly don’t understand the values that define the ultrarunning and mining communities alike. It's a kind of determination and acceptance of pain as part of the joy of the sport that not many runners ever get to experience or understand.

As ultrarunning icon Scott Jurek once stated, “I started running for reasons I had only just begun to understand. As a child, I ran in the woods and around my house for fun. As a teen, I ran to get my body in better shape. Later, I ran to find peace. I ran, and kept running, because I had learned that once you started something you didn’t quit, because in life, much like in an ultramarathon, you have to keep pressing forward. Eventually, I ran because I turned into a runner, and my sport brought me physical pleasure and spirited me away from debt and disease, from the niggling worries of everyday existence. I ran because I grew to love other runners. I ran because I loved challenges and because there is no better feeling than arriving at the finish line or completing a difficult training run. And because, as an accomplished runner, I could tell others how rewarding it was to live healthily, to move my body every day, to get through difficulties, to eat with consciousness, that what mattered wasn’t how much money you made or where you lived, it was how you lived. I ran because overcoming the difficulties of an ultramarathon reminded me that I could overcome the difficulties of life, that overcoming difficulties was life.”

Instead of making excuses and thinking of my future running as a means to a toned body and nothing more, I’ve already begun training with all my heart for the 2025 Leadville start line I know I will soon toe; I’ve found a pacer and crew, and I have every intention of crossing that finish line as well and adding yet another chunk of invaluable metal to my medal wall.

After all, it takes a true mining professional to look at an impenetrable fortress of rock and carve it away to find the gold deep inside—and I know I’ll find my gold in Leadville, a town truly as ‘tough as lead’ yet chock full of heart.

Ken and Merilee standing proudly in the stunning mining community they helped save.

Ken and Merilee standing proudly in the stunning mining community they helped save.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!