For Good Drillers, It’s All About Development

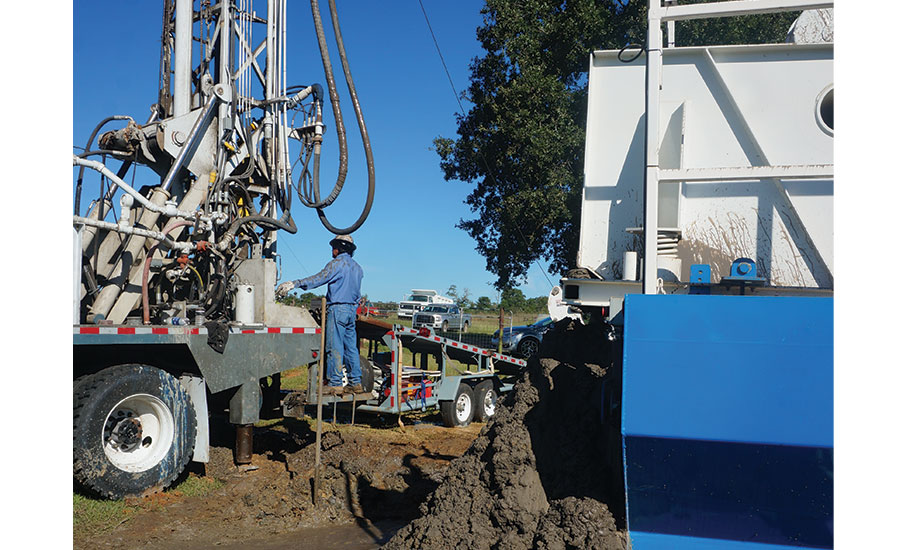

Columnist Brock Yordy advises that there will always be more than one way to complete a borehole, screen a production zone and finish the job. Being prepared and flexible in your approach increases your odds of making a successful hole. Source: Brock Yordy photos

Communication among crews, between crew leaders and managers, and with customers and regulators, is crucial to effectively finishing a job. Source: Brock Yordy photos

“I have become a driller, now what?”

That is a question I asked myself on the drive back to the shop after finishing another well. I remember wondering, what’s next? How do I become a good driller? How do I get to be as good as my father?

If you are not asking yourself what is next, then you are not progressing as a driller. However, it could be possible that you live on a one-acre island and, once you hand dug the first and only water well required, there was nothing else to learn. It is also possible to be a drill rig operator and not a driller. A drill rig operator understands all the controls and functions of a drill rig. A driller understands when and how to utilize the controls and functions of a drill rig. Last year I wrote an article called, “How Do I Become a Driller.” In that article, I outlined what I would have told my 18-year-old self on becoming a driller. Seven years of experience later, at 25 years old, I believed I was developing into a good driller. If I could go back in time to 2005, this is what I would teach my 25-year-old self on how to become a good driller.

Review Your Work and After Action Reviews

The first thing I would teach my 25-year-old self is to utilize the After Action Reviews (AAR) process. This review method was first introduced to me while working with the U.S. Army water well drillers. After every project or mission they finished, they would have an AAR to discuss all that had happened. This review process asks three critical questions: what happened, what was expected to happen and how can we improve on what we learned? Being able to reflect and review on what happened versus what was supposed to occur is paramount.

Take the time to learn from what happened on each hole and then ask, “How I can improve on what I learned?”

If I had studied each well that I completed in the detail required for an AAR, my ability to make better decisions on the next job would have increased tenfold. The difference between a driller and a good driller is accurate execution through past experiences. A driller that cannot differentiate between what was expected to happen versus what happened will continue to make the same mistakes. Compound those similar errors over seven years, and then you have to ask yourself, does that driller have seven years of experience or does that driller have one year worth of experience seven times?

Take the time to learn from what happened on each hole and then ask, how I can improve on what I learned? Once you are comfortable with the review process on each hole, take it to the next level. Start discussions with your peers and mentors about projects past and current. Don’t have a mentor? Then seek one out; there are many expert women and men in the drilling industry eager to discuss drilling situations and solutions.

Communicate

Thank goodness that in 2005 texting was not as popular as it is now! I likely would have gotten a text from 25-year-old Brock saying “lol, come on old man.” Communication is just as important as experience, if not more critical. A good driller must be able to communicate on multiple levels, from talking to his boss to those outside the company, like customers, engineers or regulators. Effective communication is driven by a good understanding of the drilling process and job completion.

As a young driller, I was always worried about answering questions asked by a water well regulator on the jobsite. I feared that I would answer a question inaccurately and get my father’s company in trouble. This fear pushed me to memorize and to stay informed of all laws, regulations and best practices. The more information I took in and the more experience I gained as a driller, the more comfortable I was talking to the regulators. Today, I would tell my younger self that regulators and project engineers are not on site to ask trick questions, but to ask questions that ensure all parties are working toward the same goal. The customer is going to have a different matter than a regulator or engineer. The customer’s most significant concern is going to be how much time it will take to complete the job and how much impact the rig and drilling process will have to their property. A good driller should be able to discuss all expectations of a project and understand the audience he or she is communicating with.

Be Prepared!

Drilling is a disruptive process, and despite how smoothly you completed the job yesterday, there is a good chance it will not be that easy today. A good driller will load out his rig and service truck with everything required to complete the job and everything that might be needed to complete a slightly different situation. An experienced driller can utilize all tools on site to manipulate the disruptive drilling process into a more controlled environment. If we had X-ray vision, then it would be easy to see that at 48 feet below the surface there is a significant fracture zone and foam drilling would be a better drilling method than mud drilling. If you are prepared and view every job with the idea that you will need to be versatile, then a change in drilling methods or utilizing loss circulation material will be easy. There will always be more than one way to complete a borehole, screen a production zone and finish the job. Being prepared with multiple options increases the odds of being successful.

Slow Down!

First off, slowing down is a concept that I have to work at every day. I do not have to go back in time to tell my 25-year-old self to slow down, I can just look at the sticky note on my monitor that says “Hey Brock, SLOW DOWN.” I believe that every drill rig control panel should have a “SLOW DOWN” sticker pasted right above the rpm tachometer. That sticker is there to remind a driller that slower and smoother will always be faster. Slower is faster because it is safer; it eliminates undue risk by ensuring that each process is completed with precision. Yes, you can trip out of the borehole fast and slam pipe into the carousel or rod box, but each time that process is rushed, the chance is taken that someone will get hurt.

Slower is faster because it is safer.

Practice and experience allow for drillers to operate faster with precision, but that speed is still within safe parameters. A driller will predict the amount of time to finish a project and will push everyone on site to complete the well in that time. A good driller understands the time it takes and adds 10 percent to ensure that job is completed safely and successfully. I would teach 25-year-old Brock that, when a problem onsite arises to first slow down, take a deep breath and assess the problem, and then choose the right solution. Fighter pilots and astronauts work most of their jobs at breakneck speeds. What makes them successful is practice and their training to access all information on hand to make the right decision in the shortest amount of time.

The drilling industry’s process of creating or teaching drillers is complicated, and as the age gap continues to widen, it will be harder to find good drillers, let alone just operators. I believe that there are days that I am a good driller and there are days I am only an operator. In reality, to be a driller versus an operator is all a mindset. A good driller is the team leader onsite. That leader’s goal is to finish the project safely, responsibly and successfully on time. It is the good driller’s responsibility to develop the next set of drillers and good drillers. If our experienced drillers take the time to teach all that they have learned to become a good driller, we can reduce the learning curve, create more drillers and start to narrow the age gap. A good driller is the individual that can take all that they have learned and pass it on to the next driller while they continue to learn right alongside them.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!