Canister Drill Sets Shaft Diameter Record on St. Louis Job

The stinger on this 72-inch canister drill followed a pilot hole down to depth on this St. Louis jobsite. Hammers from this canister were removed for later use in the 108- and 132-inch hole openers that followed. Source: Center Rock Inc.

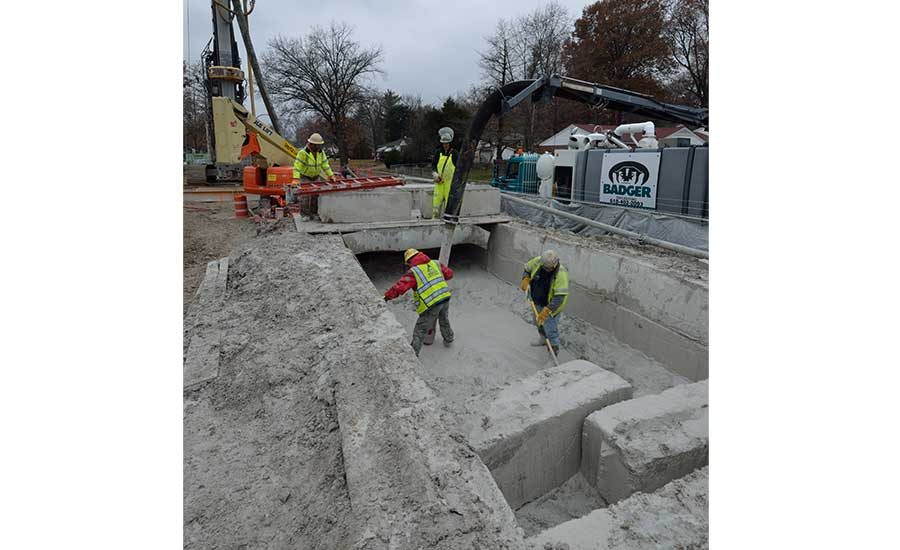

One of the Project Clear job requirements was to minimize impact on traffic and residents, since drilling was done near residential areas. Source: Center Rock Inc. photos

The Metropolitan St. Louis Sewer District (MSD), the country’s fourth largest sewer system, is upgrading its storm and wastewater infrastructure in a 23-year-long, $4.7 billion initiative called “Project Clear.” The primary goal is to improve water quality and alleviate many wastewater concerns in the St. Louis region by planning, designing and building community rainscaping, system improvements, and an ambitious program of maintenance and repair.

Historically, times of intense precipitation overwhelmed the current sewer system. Therefore, part of the system renovation has focused on building underground stormwater storage tunnels, permitting controlled drainage of runoff and preventing overflows into rivers and streams.

Construction plans for the stormwater storage tunnels called for eight vertical intake and ventilation shafts to be bored from the surface. These will then be intercepted at a depth of about 150 feet in bedrock during excavation of the 3,000-foot-long, 28-foot-diameter underground tunnel.

On this job, the reverse circulation version of the Center Rock Low Profile canister drill set a new industry record for largest canister-drilled bore at 132 inches diameter. Other bore diameters varied from 72- and 84-inch ventilation shafts to the larger intakes.

The wide-diameter pneumatic percussion tools offer one of the fastest and most precise ways to bore the shafts in hard limestone. Center Rock Inc., manufacturer of air-drilling tools, services and accessories for the global drilling, oil and gas, construction, mining and foundation industries, supplied the canister drills for this job.

Conventional vs. Reverse Circulation

The Center Rock LP drills are not conventional canister drills. Center Rock technician Dan Spiecher, onsite consultant during use of the reverse circulation canister systems, explains the advantages of Center Rock’s reverse circulation method compared to the conventional canister-drilling technique.

Both the conventional canister drill and the reverse circulation canister drill are based on individual 6-inch, low-volume, down-the-hole hammers positioned in a metal cylinder. Each hammer impacts a 7.875-inch, self-rotating hammer bit.

“A hole that takes two weeks to drill with a calyx system can be drilled in three days on reverse circulation — without working the rig hard at all.”

– Richard Soppe

The operator slowly rotates the canister during drilling to ensure DTH bits impact evenly across the bottom of the hole, to prevent the drill from bottoming out if it were left stationary. Rotation, however, marks one of the differences between reverse circulation and conventional canister drilling: Reverse circulation permits continuous rotation.

Reverse circulation’s greatest advantage, Spiecher says, is that there is no calyx to empty. “In conventional cluster drilling, every 2 or 3 feet, you empty your calyx. Sure, it only takes five to 10 minutes, but that’s still five to 10 minutes of non-drilling time for every couple feet of penetration. It adds up to a lot of lost drilling time by the end of a work shift.”

Richard Soppe, senior drilling application specialist for Center Rock downhole drilling products, says, “As we’ve seen here, a hole that takes two weeks to drill with a calyx system can be drilled in three days on reverse circulation — without working the rig hard at all.”

St. Louis Project

John Deeken is a geotechnical engineer with Black & Veatch Corporation, the construction manager for the Maline Creek project. Deeken says drilling and blasting technique for creating the shafts here was ruled out, as the project was located in a residential neighborhood.

“We could have used rock coring or a cutter head, but the drop shaft of this project is constructed within 10 feet of an existing 108-inch-diameter sewer main,” Deeken says. “We had to take precautions to avoid damage to it.”

Canister drilling offered a highly precise means to create the shafts, leaving a smooth-sided bore right on target.

Ground conditions in this 132-inch intake shaft were wet due to the proximity to the Mississippi River and high groundwater levels. “They’ve been finding shale in 2- to 6-foot layers between weathered layers of Mississippian limestone,” Spiecher says. “The 2-foot layers we can punch through. The 6-foot layers slow us down.”

Spiecher says full-face canisters could have been used, but reaming the hole to size has advantages. “Our canisters in a full-face configuration will drill it, but following a pilot hole adds more precision. And it’s also much more feasible. A full-face 132-inch canister would need about 40 hammers. That’s a lot of inventory lying around until you need your 132-inch can. This way, you can just use the same hammers you were just using for your 72-inch drill.”

The shaft was therefore widened in stages. After a subcontractor drilled a 12-inch pilot hole to 160 feet, the hole was filled with pea gravel. Pea gravel is a comparatively easy medium for a pilot, or “stinger,” to follow, yet prevented any debris from entering the pilot hole that could cause deviation during augering and subsequent canister drilling.

Overburden was removed using a Liebherr LB 36 rig with 72-inch auger and 12-inch stinger. The LB 36 is a 106-ton rotary drilling rig with a 523-horsepower engine and 440-ton maximum winching and crowd force capabilities. Then the 72-inch hole was widened by the same rig with a 144-inch auger. A 140-inch casing was set from the surface 3 feet into limestone bedrock.

After all hole locations were augured, the rig’s kelly drive was replaced with a rotary top head. The holes were reamed to final depth in the limestone using a series of Center Rock LP reverse circulation hole openers. For the 132-inch hole, the progression was from a 72-inch drill to a 108-inch drill and finally the 132-inch-diameter drill, all reaming performed using reverse circulation technique.

A 72-inch LP Canister can be run on as few as three of the 1,450 cfm, 200 psi Sullair compressors onsite at this job. To ensure ample flushing air for the record-setting diameter of this hole to depths over 150 feet, seven units were used, sending air through 3-inch hoses to a Center Rock air manifold. A 6-inch hose supplied air from the manifold to a divided valve that fed the swivel at the rotary head of the drill rig through two 3-inch hoses. Two air tubes inside the drill string sent up to 10,150 cfm of air at 182 psi to the hammers in the LP Canister.

Air exhausted by the hammers flushed fluid and cuttings at the hole bottom up through ports located at the sides of the hammer near its face. Seal bands matching the hole diameter and located on the canister above the ports prevented the returning flow from escaping up the sides of the hammer. The return flow was instead channeled up through the canister ports to a discharge hose carrying the cuttings to a temporary collection pit built of cement blocks. A vacuum truck removed the pit’s contents as called for, hauling them off for disposal.

The reverse circulation system will work in dry rock, Spiecher says, but keeping the hole wet controls dust and keeps the shale wet. “It’s a general rule of thumb in drilling to ‘keep a wet hole wet.’ It could start to choke us off if we let it get too dry.” Center Rock’s water injection system with triple piston pump can return water from the pit to the hole at 3 to 22 gpm.

Soppe says reverse circulation canister drilling proved itself much more economical than other methods of boring the vertical shafts. “One would think running seven 1,450 cfm compressors this way would be cost-prohibitive. But consider that we just drilled a hole in three days that would generally take two weeks with a conventional can drill. We’re coming out way ahead on operational costs.”

Deeken says after drilling the shafts, some of the surface casing will be partially removed to accommodate a 44-foot tall diversion structure and lined drop shaft.

The 132-inch bore in St. Louis tops Center Rock’s own record, previously held at 120 inches. However, Center Rock will take custom orders for canister drills in all diameters ranging from 24 to 144 inches.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!